France and China's Belt and Road Initiative

Under President Macron, France has staked out a positive but principled position towards China's BRI.

When China’s President Xi Jinping launched his flagship project on the “Silk Road Economic Belt” in Astana in the fall of 2013, followed by the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” in Jakarta a month later, few people in France took notice, except perhaps for a few experts in academic circles or research institutions focusing on China.

There is no denying that it took a long time for the French government (and other French economic actors) to take the issue seriously and start thinking of a possible response to the Chinese project. This may be considered as a lack of foresightedness, but there were many good reasons for France to overlook the project and underestimate its potential impact, at least in the first couple of years after its launch.

First, to be fair the Chinese project was initially so unclear that it was extremely difficult to fully grasp its scope and objectives. What eventually came to be known as the “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) and later as the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) was at the time a relatively fuzzy concept. Although it was clear that the project involved infrastructure development and investments with a view to enhancing connectivity between China and Europe through a multiplicity of economic corridors, the exact way of achieving the objective remained to be defined. Actually, what made the project unique and unprecedented (and hence difficult to assess) is the fact that the concept was launched even before its exact content was defined (and China’s partners were even frequently encouraged to provide ideas on how to achieve it). Never in recent history has a project been launched by a government with so much determination, so much investment in its national and international promotion, but with so much ambiguity.[1]As a result, the concept itself has continually been adjusted over time by the Chinese authorities, leaving China’s partners unsettled.

Moreover, France was initially not considered as a potential target, and no single project was envisaged on its territory. There was thus little reason to pay too much attention.

As time went by, however, the project became increasingly concrete (with the first trains connecting Wuhan and Lyon in April 2016 for instance) and with some EU countries being explicitly targeted (with the construction of a high-speed rail line between Budapest and Belgrade for instance), the need to develop a strategic response at the national as well as at the European Union level became more pressing.[2]On top of it the immaterial dimension of the project became increasingly clear.

A positive …

Overall, the reactions on the French side can be said to be relatively positive. Of course, a distinction needs to be made between the local and the central government’s level as well as between the private sector’s and the government’s reactions to the Chinese project. Broadly speaking, the former reactions tended to be more enthusiastic than the latter. At the local level, the second largest city in the country, Lyon, welcomed the arrival of the first Belt and Road train connecting it with Wuhan in April 2016, and other large cities such as Marseille also tended to look at the BRI more as an opportunity than as a threat.

A number of companies share this positive stance; such is the case in particular of logistic companies such as CMA CGM LOG, the logistic arm of the CMA CGM Group, which aims to become a key player in the international supply chain management market and a real reference for Silk Road services between China and France.

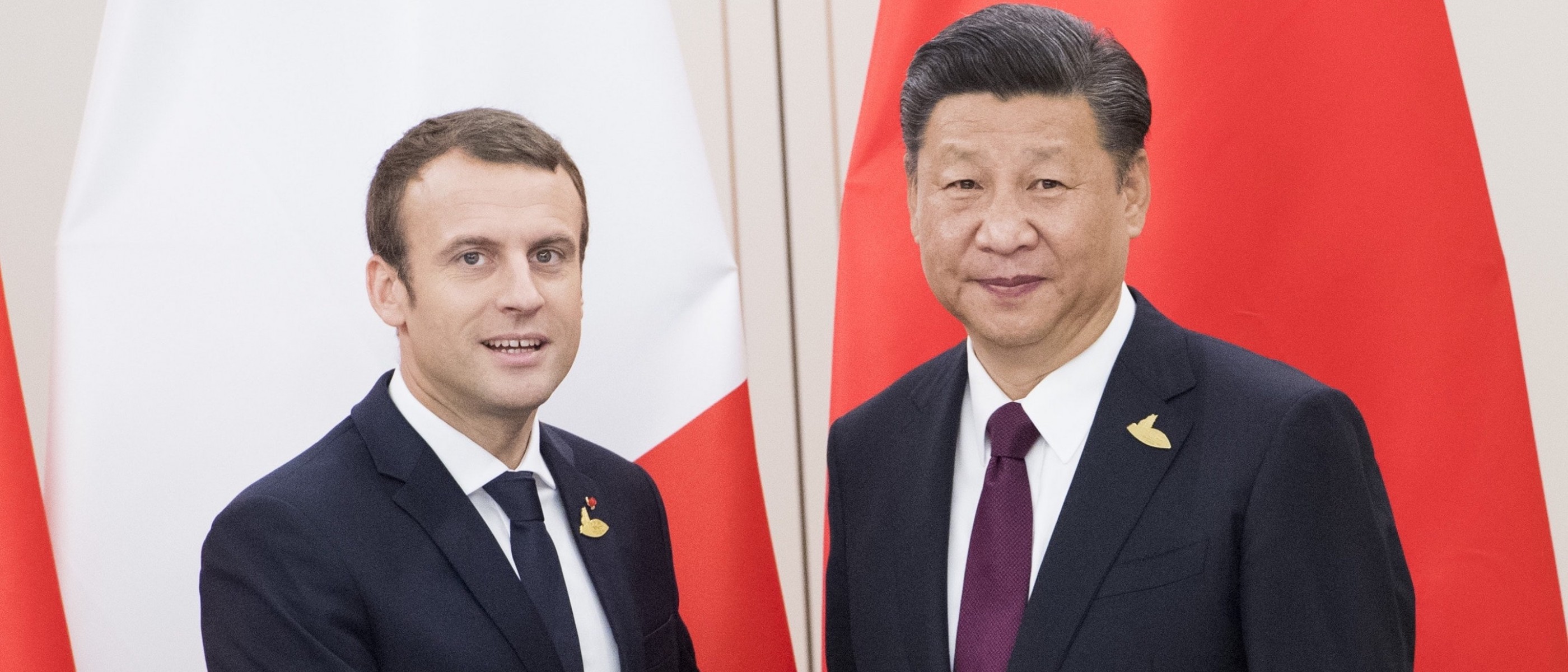

At the central government level, although the BRI did not top the list of priorities until recently, the approach to the BRI was overall favorable. As early as June 2015, then Minister of European and Foreign Affairs, Laurent Fabius, was quoted as saying: “We welcome the New Silk Roads Initiative[3].” A couple of years later, President Macron did not express a different view when he reasserted France’s support to the Chinese project during his first trip to China.

… yet principled position

However, France’s support is not unconditional. During his visit to China in early 2018, President Macron defined the conditions more explicitly, calling in particular for reciprocity and stressing that “Silk Road cooperation must work in both directions”.

In concrete terms, unlike Italy, French authorities have not signed a Memorandum of Understanding on BRI and do not plan to do so in the near future; instead they are seeking cooperation on a project-by-project basis with a view to raising growth potential in host countries. To that end the emphasis is placed first and foremost on economic cooperation, primarily between French and Chinese companies in third countries. For the time being, although there is an agreement on the overall framework for potential cooperation in third countries, no single project has yet materialized simply because the conditions could not be met.

Moreover, the French authorities insist on the benefits that French (and European) businesses should be able to reap from such joint projects. The fact that the vast majority of Chinese financing has in the past gone to Chinese companies, is clearly perceived as highly problematic and not in line with the supposed “win-win” logic often stressed by their Chinese counterparts.

Another major concern expressed by the French government relates to the risk for countries receiving financing from China to be dragged into a “debt trap”, as was the case in Sri Lanka for instance. As a result, the French government places a heavy emphasis on the need to follow the “G20 Operational Guidelines for Sustainable Financing” agreed upon in 2017, the objective of which is to ensure that creditor and debtor countries’ lending and borrowing practices facilitate sustainable public debt levels.

More recently, President Macron has also stressed the need for a European response rather than a mere national response: "For many years we had an uncoordinated approach and China took advantage of our divisions. An awakening was necessary", Macron said a couple of days before Xi Jinping’s visit to Paris.

To be tough does not mean to be negative

In contrast to what is often claimed, there is no systematic opposition to BRI in France, but the emphasis is consistently placed on the conditions to be met for the cooperation to be fruitful and really of a win-win nature.

Interestingly, the tough French stance has not led to any pushback on the part of China and a number of large contracts were signed during President Xi Jinping’s recent visit to Paris, suggesting that the French approach may after all prove to be more rewarding than the Italian embrace of China’s BRI.

[1]For more details on the methodology of BRI, see A. Ekman et al. (2018), « La France face aux Nouvelles routes de la soie chinoises », Etudes de l'Ifri, Ifri, Paris, octobre.

[2]A number of reports were issued in 2018 by the French Treasury as well as by the French Senate in particular.

[3].Speech delivered by Laurent Fabius on June 12, 2015 in Rouen for the opening ceremony of the China-Normandy Forum.

This article and associated images have been reproduced from the website of the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI).

Available in:

Regions and themes

Share

Related centers and programs

Discover our other research centers and programsFind out more

Discover all our analyses

RAMSES 2024. A World to Be Remade

For its 42nd edition, RAMSES 2024 identifies three major challenges for 2024.

France and the Philippines should anchor their maritime partnership

With shared interests in promoting international law and sustainable development, France and the Philippines should strengthen their maritime cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. Through bilateral agreements, expanded joint exercises and the exchange of best practices, both nations can enhance maritime domain awareness, counter security threats and develop blue economy initiatives. This deeper collaboration would reinforce stability and environmental stewardship across the region.

The China-led AIIB, a geopolitical tool?

The establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016, on a Chinese initiative, constituted an attempt to bridge the gap in infrastructure financing in Asia. However, it was also perceived in the West as a potential vehicle for China’s geostrategic agendas, fueling the suspicion that the institution might compete rather than align with existing multilateral development banks (MDBs) and impose its own standards.

Jammu and Kashmir in the Aftermath of August 2019

The abrogation of Article 370, which granted special status to the state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), has been on the agenda of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for many decades.