China and the “Definition Gap”: Shaping Global Governance in Words

Increasingly, China’s diplomacy is using key words commonly used by liberal democracies, but the meaning differs greatly. This evolution is changing the terms of the debate without changing a single term.

The Widening “Definition Gap”

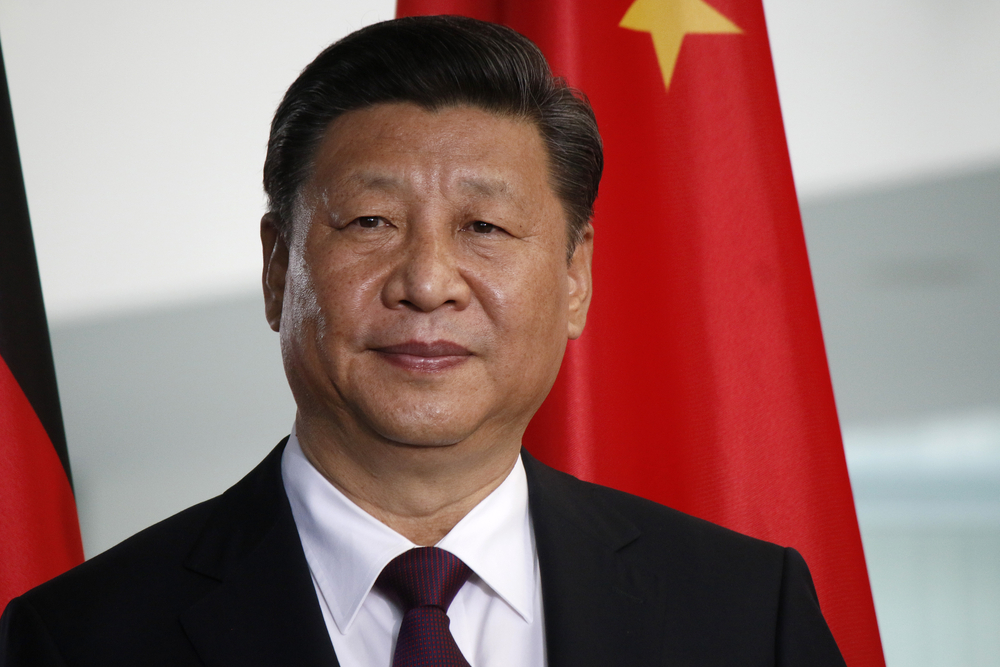

China has very actively participated in high-level multilateral gatherings in recent years. Since he became president of the People’s Republic of China five years ago, Xi Jinping has managed to position himself as the key introductory speechmaker at these events, whose declarations are often the most covered and discussed by international media, from the World Economic Forum in Davos to the G20 Summit in Hangzhou. This is part of Xi Jinping’s policy to “spread China’s voice well,” to “present China as a builder of world peace, a contributor to global development, and an upholder of international order,” as he urged Chinese media and think tanks to report on repeated occasions over the last two years.

In concrete terms, spreading China’s voice well materializes in Xi Jinping’s speeches at multilateral summits in two ways: repeated use of China’s new official concepts and key expressions (such as “Community of Common Destiny” or “Belt and Road Initiative”), and increased use of words and expressions that are widespread and consensual in multilateral forums. Xi now frequently talks about “economic globalization” (mentioned more than 30 times in Xi’s visit to Switzerland in January 2017), “connectivity” (mentioned in all “Belt and Road” forums since 2013), or “rule of law” (mentioned on a frequent basis since it was established as the theme of the 4th plenum held in October 2014). China is currently harmonizing its international communications with the help of Western public relations agencies and advisers, better placed to know what a Western audience prefers to hear and to adjust China’s official communications in accordance.

As a result of this adjustment, the lexical gap is narrowing: Chinese leaders and their foreign counterparts are increasingly using similar words in international settings. China’s official communications today are much softer than 50 years ago, when Mao Zedong or Zhou Enlai were openly calling for the “struggle against US imperialism and its lackeys” (or “its running dogs”). It is noteworthy that such discourse softening mainly concerns China’s international communications. A significant gap remains between Chinese domestic and international communications today. Abroad, Xi does not use keywords of the red rhetoric such as “Western hostile forces” or “mass line campaign”—which are still used today in intra-Party and domestic communication.

If the lexical gap is narrowing, what I would call the “definition gap” is widening: Chinese leaders and many of their foreign counterparts are using the same words but actually mean very different things. For instance, the definition of the “rule of law” differs between China and the European Union. Chinese leaders actually refer to “socialist rule of law,” under the leadership of the Communist Party, and aim at establishing “a system of socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics,” as Xi stated in the opening ceremony of the 19th CPC National Congress. If these definitions gaps are among the most obvious, many others exist: China’s definitions of “fight against corruption,” “the Internet,” “civil society”—among others—differ greatly from the ones most democratic countries generally attach to these terms.

Concrete Consequences: from image improvement to document signing

The widening definition gap has significant concrete consequences. The first consequence is that a new perception of China emerges among part of the foreign policy, academic and media community, which takes Chinese official discourse at face value. For instance, following the 4th Plenum that was held in October 2014 on the topic of the “rule of law,” a significant number of commentators saw this as an indication that China was actually moving towards the implementation of the rule of law—as it is understood in their own countries. More recently, Xi’s Davos speech in January 2017 led to a diversity of analysis and interpretations, some of them perceiving it as a clear indication that China will become more “free-trade” oriented, and saw the speech at a turning point towards China’s further economic opening up. Overall, China’s discourse softening is perceived as a sign that China increasingly share with many liberal democracies a similar approach to the world and its current challenges.

A second consequence is that a significant number of joint statements and communiqués signed with China—bilateral or multilateral—are now based on misunderstandings. In general terms, misunderstandings have always existed in the history of diplomacy, because of gaps of perceptions, perspectives, or just translation of languages that are sometimes too different to find suitable equivalence in the terms used. In some instances, signatories may play on misunderstanding to reach a consensus; this is part of the diplomatic tradition. In these cases, the “definition gap” is well-known on both sides, and is helpful in accommodating diverging interests or expectations at home. This does not necessary represent a problem when the signing parties are aware of it. But increasingly, as China’s diplomacy integrates keywords that are commonly used by other diplomacies, the misunderstanding is not fully acknowledged by foreign counterparts. For instance, when China pushed for the signing of documents on anti-corruption cooperation at the G20 summit held in Hangzhou in September 2016, and several documents on these specific issues were actually signed, not all signatories and their staff were fully aware of China’s definition of “corruption” in the current context of its vast anti-corruption movement at home and abroad. From the Chinese government perspective, these documents were first and foremost aimed at internationalizing Xi’s strict and highly political “anti-corruption campaign” and launching a new wave of “fugitive repatriation and asset recovery,” in the framework of his “fox hunt” campaign. Xi stated at a press conference following the summit, “(These) will leave corrupt officials no place to hide in G20 members’ territories and in the world at large." For sure, France’s then president François Hollande had a different idea in mind when he declared on his way to the G20 that « the intensification of the fight against fiscal evasion and corruption » would be priority.

A third consequence is that the implementation of such statements lead to international actions that were not initially agreed or supported by states involved, had they known what it actually meant when the document was signed. For instance, China aims for extradition and mutual legal assistance treaties with democratic countries to eradicate “safe havens” for Chinese fugitives, and has successfully signed such treaties with an increasing number of countries—which were not fully aware that China’s definition of “anti-corruption” was different from theirs, and that Beijing would be willing to use covert police operations to pressure citizens into returning—extradition treaty signed or not. In broader terms, the signing of joint statements based on definition gaps may have significant consequences as China is promoting global law enforcement in line with its domestic legal practices and priorities.

In light of these observations, the widening definition gap might ultimately be China’s most efficient way to promote its interest in multilateral settings: it is changing the terms of the debate without changing a single term.

Reducing the Definition Gap : focus on the practice of diplomacy

A consciousness is now emerging among diplomatic circles about China’s communication activism in the Xi era, and in particular its push for the internationalization of key official concepts, after recent cases went well-noticed, such as the inclusion of “Human Community with Common Destiny” into a UN Security Council resolution on Afghanistan last March. Other similar cases are likely to occur in the coming years, as China’s diplomacy is concept-based and incorporation of key official concepts in multilateral communications is a clear, well-defined objective of China’s proactive diplomacy in multilateral gatherings. Such objective is part of China’s ambition to have more say in international affairs (国际话语权; “guoji huayuquan”) and to enhance its soft power, in broader terms. Already, it is not uncommon today to hear diplomats and officials from European countries regretting the appearance of a Chinese keywords or concepts in a joint document their country has signed with China in recent years—some accusing Chinese officials’ relentless attempts to integrate such words, which ultimately became successful, sometimes for anecdotal reasons (tiredness to fight/negotiate back after so many attempts; discussions taking place late at night, etc.). In the long term, after repeated attempts, China might successfully convert its official concepts into diplomatic keywords of reference, used by an increasing number of international actors and organizations, but this remains hypothetical as spotting such concepts and negotiating their appearance in joint documents might become easier for foreign diplomats in the future, as China’s communication objective and key official concepts become better known, and therefore easier to spot.

Much less easy is to deal with the definition gap, which is by nature harder to notice. Awareness is possible after extensive analysis of China’s official language and public diplomacy practices, which requires time. And politicians and high-level representatives who are ultimately the signatories of these documents have limited time to pay attention to what may at first sight seem mere play on words and rhetorical/conceptual debates, with no apparent practical consequences; and their advisers have usually more pressing, concrete issues to deal with. Even when a significant number of China watchers—diplomats, researchers, or journalists—are fully aware of this gap, the awareness rarely reaches political level. Reducing the definitional gap is therefore a difficult task, because it does not only require full identification of the gap among middle-level officials and practitioners of diplomacy, but also necessitates their ability to inform higher-level policy-makers—those who will ultimately sign joined statements—about it. In general terms, it is hard for an audience who is not familiar with China to read in between the lines of Chinese discourse, for understandable reason: China’s propaganda apparatus and methodology differs greatly from the communication landscape known in countries with different political history and current political context.

Interestingly, researchers and officials from countries who previously and directly experienced Soviet-style propaganda, such as Poland, often appears better armed to read in between the lines of Chinese official communication, which has been highly been inspired by communication techniques of the USSR. But countries are unequally armed to address the definition gap. The most vulnerable are often diplomats from small diplomat corps (in total number of staff), who cannot rely on a large team of China-specialized colleagues and experts to help them conduct their mission and read between the lines of China’s communication and actions. As a matter of fact, significant number of countries are facing a deficit of in-house China expertise.

Academics and experts are also vulnerable, as they are increasingly invited by China to participate to the large number international think tank forums and track 1.5 gatherings that it organizes on its territory and abroad. It is common in these forums that the Chinese organizers encourage them to sign joint communiqués or provide an international endorsement of Chinese concepts and definition that they do not necessary adhere to. This materializes in various ways: pressure for signing such joint communiqués, late disclosure and circulation of the first draft, state-owned media underlining—sometimes without their consent—positive receptions by “foreign experts” of China’s concepts or reforms pressure for being part of “think tank network” launched at the initiative of China under the umbrella of a national concept (“Belt and Road”, “connectivity”, etc.)—without full communication on the objectives. Many of these situations represent challenges, if not traps, for participants who are not familiar with diplomatic practices and their subtleties (academics, but also representatives from local governments, NGO or the private sector, among other actors with which China’s diplomacy increasingly engage).

In this context, clarification of some practices of diplomacy is needed in order to better identify and address the definition gap, for instance, by making sure that the draft communiqués are sent in advance to be carefully read, analyzed, and the terms defined where necessary. Helpful lessons can be learned from previous multilateral summits and forums, such as the Belt and Road Forum held in Beijing in May 2017, which raised many issues in this respect, and constitutes an interesting case study that can be learned from. In addition to the practice of diplomacy, the definition gap poses questions related to ethics of diplomacy in broader terms: intellectual integrity and transparency of the organizers of track 1.5 and 2 events—in particular towards participants who are not professionals of diplomacy.

Such clarification would be helpful as Beijing has been promoting a very active “forum diplomacy” in recent years: China does not only participate more actively in existing multilateral forums, but also creates new ones with the ambition to compete with well-established forums (such as the Boao forum for Asia, an annual conference initiated in 2001 following the model of the Davos World Economic Forum, the Xiangshan forum, regional security conference inspired by the Shangri-la Dialogue, or the many “Belt & Road forums,” of various formats and levels, conceived to become multilateral gatherings of reference in the long term).

An Emerging Competition of Definitions

In the long term, a risk is that Chinese definition becomes definition of reference in many countries, as China invests massively in its cooperation and communication towards developing and emerging countries. The definition of the term “development” is already at the center of a strong communication and ideological competition between China and many developed countries. Such competition is likely to intensify in the coming years, as China is increasingly promoting an alternative model of development and governance in the world, explicitly pointing at the weaknesses of Western liberal democratic systems and positioning itself, in contrast, as an alternative “solution” provider (according to the official concept of “China solution,” or zhongguo fang’an, 中国方案). This discourse has been promoted—first and foremost towards developing countries, but also, increasingly, towards emerging and developed countries—through training programs directed at officials, politicians, engineers, technicians in various fields, among other professionals, and have often included an ideological component in addition to practical training. Throughout the years, China has also promoted its image as a “solution” provider through its international media outlets, now broadcasting in local languages in a large number of countries and progressively becoming media of reference (in particular in countries where national media landscape is weak/facing financial difficulties).

Chinese definition may become definition of reference with the help of some developing countries, but also key partners who share similar definition and approach to key issues. For instance, China shares with Russia close perception and definition of the “Internet,” “Terrorism,” or “Security,” to some extent. A competition of definitions is currently noticeable in some multilateral gatherings. For instance, at recent regional security dialogues held in the Asia Pacific Region (such as the 2017 Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore or the 2017 Seoul Defense Dialogue, among others), both China and Russia have been promoting new Security concepts, and more generally proposed a new approach and definition of the term “security” which were compatible with their views.

In its active participation in multilateral gatherings and objective to become a norm-, concept- and definition-setter, China counts on the support of developing and emerging countries, foremost amongst them Russia, with whom it shares a vision of a post-Western world order. China’s communication activism is part of its broader ambition to become a norm- and standard-setter. Beijing hopes that it can set new standard, concepts and definitions of reference for the region and the world, that can ultimately replace those “imposed by West”– as seen from Beijing. From that perspective, China may become an “alternative definition” setter, as much as an “alternative standards” and “concepts” setter. In this context, “alternative definition” is a phenomenon worth analyzing per se, and taking into account the broader “alternative” trend that is emerging.

In broader terms, China’s traditional antagonism against Western liberal democracies—and the United States first and foremost—continues to shape much of its foreign policy discourse and orientations. Such antagonism has actually been reinforced in the Xi era. In addition to the promotion of an alternative model of development, China is promoting an alternative model of international relations (“new type of international relations”) –based on economic and security partnerships rather than alliance systems (and certainly not a US-led one). Xi has started to do so in the Asia-Pacific region in the first part of his mandate (in line with China’s white paper on its policies on Asia-Pacific security cooperation, published in January 2017), and is likely to continue to promote the development of such alternative partnership system in the region and beyond in the second part of his mandate, with its own definition and conceptualization of “security”.

In this context, reducing the definition gap can be helpful to clarify positions and approaches on a diversity of regional issues, from the DPRK issue (what does “freeze” mean? What does “sanction” or “pressure” mean?), to the South China Sea issue (what does “freedom of navigation” mean? What is “militarization”?). The list is endless. Such clarification process is already conducted in many semi-official or informal dialogues such as track 1.5 and track 2 exchanges. Sometimes, the outcome of bilateral dialogues is limited from the very beginning, precisely because of the existence of the definition gap. For instance, in France, there is an understanding that China and France’s definition of terrorism are significantly different. And track 2 and 1.5 exchanges on the topic often start by an underlining these differences, which were frequently seen as an obstacle for cooperation on a constructive basis. Still, acknowledging the definition gap is helpful as it is a prerequisite to acknowledging divergences of approaches towards a specific issue.

Global Governance: definitions at the core of strategies

Beyond addressing specific issues, definition clarification may be an efficient way to contribute to the ongoing global governance restructuring process. Currently, among Xi Jinping’s top priority is the promotion and implementation of China’s global governance strategy, which concerns a diversity of institutions and go far beyond global economic governance. it also concerns global environmental, cyber, security, or cultural governance. It is therefore timely to jointly clarify definitions of the issue that countries are trying to “govern” or address together. The term “good governance” itself will increasingly be subject to definition competition, as China appears more confident in stating that the Chinese political system is the best.

In recent years, calls for “like-minded” countries to preserve the rule-based order have been increasingly numerous, with many diplomatic corps (such as Japan, the United States, South Korea, Australia or European countries) encouraging dialogues and exchanges among such country grouping on the topic, and on global governance in broader terms. But beyond the US alliance system, what bind the “like-minded” countries are often subject to debate. Underlining the fact that they share common definitions might be a more precise and less controversial argument that the discourse on “common values,” which is perceived by some—first and foremost the Realists—as an expression that is too often used in international settings for the sake of national interests.

In practical terms, “like-minded” countries may start to shape their current approach to global governance by agreeing on “common definitions”—starting by simple one-word terms that are general enough to be at the basis of governance (cybergovernance, cultural governance, etc.): What does “Internet,” “Art,” or “Culture” mean? Although China does not provide official definition of these words—and is unlikely that it will in the future—a close look at official communications provides some useful indications, and confirms the existence of a significant definition gap. For instance, on “Internet,” the “International Strategy of Cooperation on Cyberspace”, published in March 2017, underlines the “Principle of Sovereignty and reminds the state-centricity of Chinese definition of the “Internet,” and therefore of cybergovernance. China’s definition of the “Arts,” and of the role of state in supervising them, also defers greatly from most liberal democracies. According to the Chinese government, writers and artists should create works that “extol the Party. China’s official communication provides elements of clarification of some definition, and analyzing it and identifying the gaps is the responsibility of those who have the time to read and analyze Xi’s speeches and other official Chinese documents–primarily policy-oriented academics and experts of China.

Even with a closer analysis, a certain degree of ambiguity will continue to surround the definition of key words used by Chinese diplomacy. Not everything should or can be defined, but at least some clarification would be beneficial not only to avoid misunderstanding with China, but to fine-tune democracies’ common vision and strategy of global governance. If countries might have difficulties to agree on a precise, fixed, and potentially biding definition, they might more easily agree on a broad definition that gives an indication on the degree of involvement—or the limits of this involvement—of the state in these fields.

This process is likely to raise the question of the universality of definitions, at a time when China defines most of the terms “with Chinese characteristics” (“Human rights with Chinese characteristics,” “think tanks with Chinese characteristics,” etc.) and seems to adopt, when promoting its own definition, a relativistic approach to definition-making, considering that each country has the right to define words as it wishes, based on its unique history, culture, political system, etc.

In any case, addressing the definition gap and agreeing on common definitions is a long and complicated task that requires strong political will, at a time when Chinese diplomacy is very actively pushing for its own. However, if such a gap is not addressed today, the risk exists that in few decades time, the definition of the key terms of reference used in international settings will change in a direction that was neither anticipated nor wished, reshaping the terms of the multilateral debate. As a result, another, more anecdotal, risk emerges: many senior European or US politicians and diplomats may write in their memoirs in 15-10 years’ time, “that was not what I meant!”—referring to terms of key joint statements they are signing with China today.

Read the article on theasanforum.org

Media:

Share