Energy Union: What's Inside the Defence Walls?

Conflicts in Ukraine and Middle East are giving resonance to the proposal for an Energy Union, originated by Poland, and, initiated by the European Commission. Indeed, access to affordable energy stands as a major concern for all EU citizens and becomes, as such, a strong political argument for the Juncker Commission to back-up an Energy Union.

Born out of the ashes of the Barroso – Ashton missing “energy diplomacy”, the Energy Union aims to build new defence walls in external relations. But, diplomatic action is not the sole recipient for success. What challenges lie inside the new defence walls of the Energy Union?

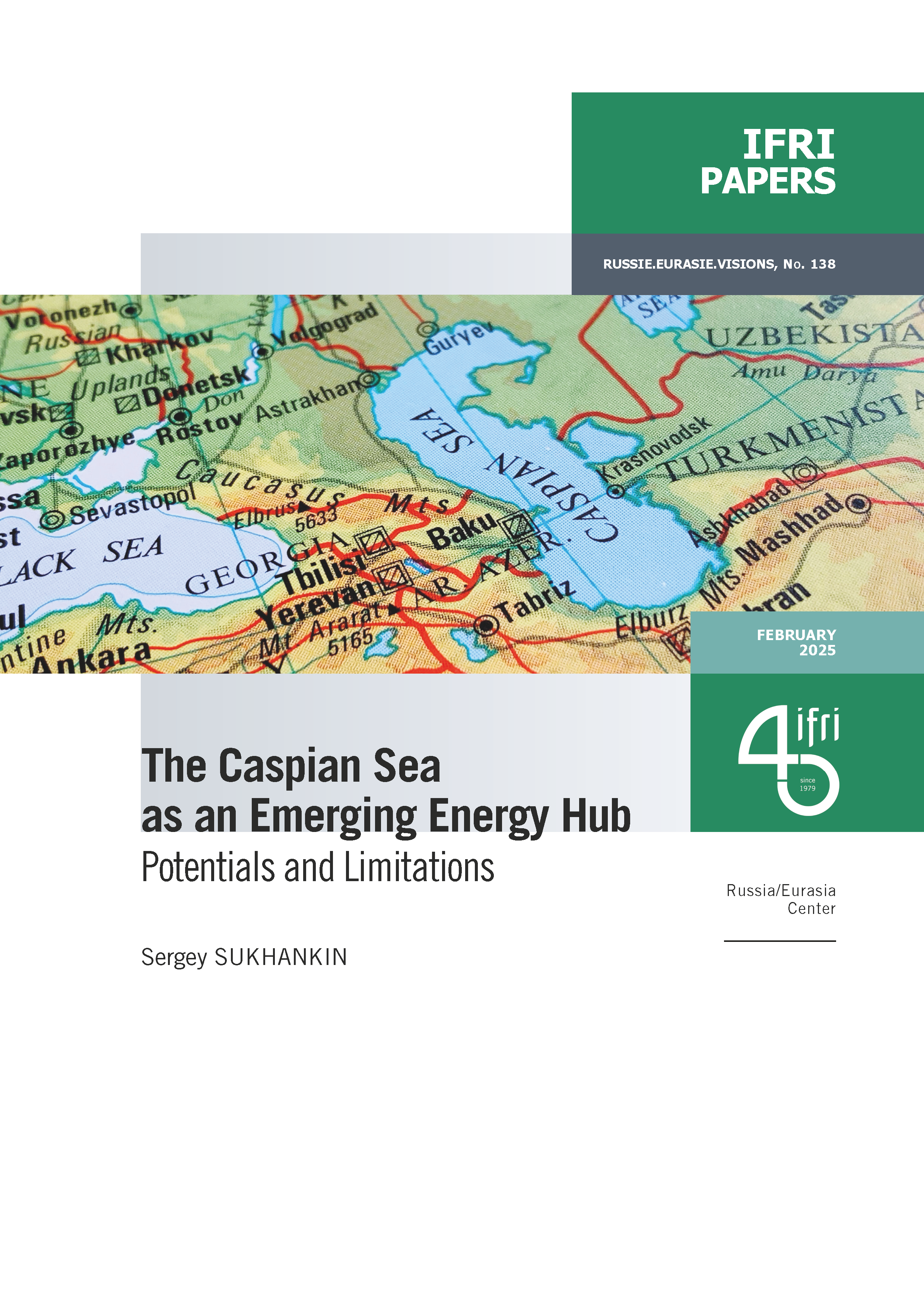

Vice President for the Energy Union, Maroš Šefčovič, together with High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Federica Mogherini, are sharing competences in building the diplomatic side of the Energy Union. Extending from the European Energy Security Strategy communication[1], devised on the back of Russia’s threats to cut Ukraine’s gas supply, the Energy Union signals a turning point to external energy trade partners - mainly its major gas supplier Russia - that the EU could not continue a “business as usual” approach to gas import contracts[2]. The Energy Union’s diplomatic centre of gravity remains mainly oriented towards Eastern Europe. Increased diversification of supply, more competition and flexibility should be framed in the EC’s relationships with its outside partners[3]. To that extent, the Commission is proposing to review intergovernmental agreements in the field of energy, enforcing compliance with unbundling rules and yet to define security of supply criteria. Already, the Energy Union is ready to give its political support to energy projects in the Southern Corridor and East Mediterranean region, including in Algeria. The revision of the Energy Community, bringing together Southern European and Black sea countries[4], in aligning energy legislation towards the “acquis communautaire” of the EU third package, will be an important aspect of the Union. Looking East, Turkey’s energy and transit sector will be brought closer to the Energy Union. Looking West, High Representative for Foreign Affairs Mogherini recommended including an energy package within the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership agreement in discussion with the USA.

On the road to the Paris Climate COP21 Conference, the EC’s DG Energy-Climate is engaged diplomatically. But, so far, the intended nationally determined contribution (INDC) to the Paris Conference as submitted by the EC, are in line with the 40% reduction in greenhouse gases to 2030[5], and the EC’s long term commitment of 80-95% reduction to 2050, below 1990 levels. Consequently, the Energy Union does not raise the EU’s long term climate ambitions.

Inside the defence walls of EU diplomacy, the Energy Union’s challenges lie in its regional implementation. Across the 28 Member States, the Energy Union’s regional dimension comes all down from an improved infrastructure interconnection, through the revision of the Gas Security of Supply regulation, to the focus on system security and cross border exchanges in electricity markets[6], where renewable integration is creating regional imbalances. To this extent, a new European electricity market organisation (market design) will be proposed this year and followed by legislative proposals in 2016. The Energy Union’s regional dimension also encompasses the regionalisation of European system operators’ associations (ENTSOe/ENTSOg). The Juncker Commission and the Energy Union proposes a “step by step” approach to the achievement of the single energy market, financially supported by the Juncker Plan, and the 248 Projects of Common Interests situated in priority corridors covering 2014-2020. Supervisory role will be given to the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators’ (ACER). All these elements will be important factors of regional market integration and enhanced physical cross border exchanges.

The Energy Union is not moving towards more federalism, and as such, may not meet all the expectations of those who were calling for a single European energy policy. While not considering internal institutional reforms, the Energy Union is reasserting the rules of the game around a new governance of existing energy policies and a stronger focus on regional integration.

[1] SWD(2014) 330 final

[2] Brookings Institute, “Business As Usual European Gas Market Functioning in Times of Turmoil and Increasing Import Dependence”, October 2014.

[3] Oxford Energy Studies: “Does the cancellation of South Stream signal a fundamental reorientation of Russian gas export policy?”, January 2015.

[4] Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Serbia and Ukraine.

[5] “The Paris Protocol – A blueprint for tackling global climate change beyond 2020”, COM(2015) 81 final

[6] 10% interconnection target equivalent to installed capacity to 2020 – rising potentially to 15% in 2030

Available in:

Regions and themes

Share

Related centers and programs

Discover our other research centers and programsFind out more

Discover all our analysesAI, Data Centers and Energy Demand: Reassessing and Exploring the Trends

The information and communication technologies sector today accounts for 9% of global electricity consumption, data centers for 1-1.3%, and artificial intelligence (AI) for less than 0.2%. The growing energy demands of cloud services first, and now AI workloads (10% of today’s data centers electricity demand), have exacerbated this trend. In the future, hyperscale data centers will gain shares amongst all kinds of data centers and AI will probably account for around 20% of data centers electricity demand by 2030.

Unlocking India’s Energy Transition: Addressing Grid Flexibility Challenges and Solutions

India is rapidly scaling up its renewable energy (RE) capacity, adding 15–20 GW annually, but the ambitious goal of 500 GW of non-fossil capacity by 2030 is at risk unless the pace accelerates.

Europe’s Black Mass Evasion: From Black Box to Strategic Recycling

EV batteries recycling is a building block for boosting the European Union (EU)’s strategic autonomy in the field of critical raw minerals (CRM) value chains. Yet, recent evolutions in the European EV value chain, marked by cancellations or postponements of projects, are raising the alarm on the prospects of the battery recycling industry in Europe.

The New Geopolitics of Energy

Following the dramatic floods in Valencia, and as COP29 opens in Baku, climate change is forcing us to closely reexamine the pace—and the stumbling blocks—of the energy transition.