More Europe in the face of realpolitik’s return? French perspectives on 30 years of German reunification

The current geopolitical situation has disrupted the European and global order, which were both consolidated in the 1990s and have been key factors in the modern German model. The Franco-German duo is currently facing new challenges and it will have to respond appropriately in a time when the EU’s global influence is shrinking in the face of what some analysts call a “new Cold War”.

On October 3rd, 1990, Germany regained its full sovereignty through reunification. This was a defining moment for Germany, Europe and the entire world. Positioned at the centre of Europe, Germany became a major arena of rivalry during the Cold War and was then in the spotlight of world politics. The reunification marked the transition from a world divided into two blocs to a “new world order” dominated by the United States, which has revealed itself to be increasingly unstable. Moreover, the end of the partition of Germany paved the way for the unification of Europe through the enlargement of the European Union. At the same time, Germany gradually became Europe’s leading economic actor.

For France, Germany’s mounting confidence following its reunification raised concerns about its destabilising potential regarding Europe’s equilibrium. France perceived potential further enlargements and Germany’s growing influence in Europe as factors in its own potential marginalisation. At the same time, the “Franco-German couple”, which had already established itself as the European driving force during the Cold War, could accelerate the pace of European integration after 1990. Nevertheless, with the accession of states from Central and Eastern Europe and the European institutions’ growing competencies, the “Franco-German couple” must constantly readapt and assert itself as a compass for Europe in order to remain relevant.

[...]

Germany’s regained post-Cold War confidence

Reunification was a turning point (Wende) that allowed Germany to regain self-confidence. It was the first step towards Germany’s “normalisation” into a “nation like any other”. German unity meant that Germany had recovered its full sovereignty “over internal and external affairs” and that it could rebuild constructive relationships with its neighbours. However, the weight of history gave it a responsibility and a duty to remember, which explains its reluctance to commit itself too assertively on the international level.

[...]

Europe’s centre of gravity shift and its repercussions on France

Franco-German relations are marked by the three bloody wars of 1870-71, 1914-18 and 1939-45. The rivalry between these two powers was later to be a determining factor in the construction of what was to become the European Union. This construction process was an attempt to convert hostile relations into a project of peace and prosperity which is what makes the Franco-German relationship, at the centre of the European Union, a “special relationship”. However, at the time of reunification, German unity raised concerns in France, which feared the return of a Germany eager to dominate Europe. French newspapers such as Le Monde published the headline in 1992: “Should we be afraid of Germany?” During the Franco-German summit in Bonn between November 2nd and 3rd 1989, François Mitterrand replied to that question by saying, “No, I am not afraid of reunification.” In a survey conducted in September 1989, 75 per cent of French people also answered positively to the question “Do you think that the German demand for German reunification is legitimate?”

[...]

Rising post-Cold War challenges

Faced with the concerns of France and other European partners about the effects of reunification, Germany agreed to sacrifice the Deutschmark in favour of a common currency, the euro. This went hand in hand with further European integration, which gained momentum in the 1990s through the Treaty of Maastricht (1992) and the Treaty of Amsterdam (1997). However, it was a stony path. The war in Yugoslavia erupted in the EU’s neighbourhood and the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe, drawn up with a view to be adopted 15 years after German reunification, ultimately failed. The Constitutional Treaty was replaced by the Lisbon Treaty, abandoning the mention of European symbols (common anthem, flag, motto). External shocks also affected the EU, such as the economic and financial crisis of 2009, the migration crisis of 2015, and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. On top of such uncertainty, various geopolitical challenges can also be added. These include growing Sino-American rivalry, on which the EU must endeavour to take a clearer stance if it does not want to become a collateral victim of the resulting world repolarisation. Of course, the war in Ukraine is also causing tremendous issues for Europe and its future.

[...]

The Zeitenwende and Germany’s new inclination towards more assertiveness

Heightened tensions at the international level, which are only increasing with the war in Ukraine, call into question a certain number of policy fundamentals. Energy policy, economic policy but also foreign policy are concerned. This repolarisation of the world represents a challenge of such magnitude that it cannot only be tackled at the national level but must also be assessed on a European scale. The geopolitical context and reorientation announced by Olaf Scholz on February 27th 2022 in a speech before the Bundestag are likely to change Franco-German and European priorities. Scholz’s speech articulated Germany’s intention to bolster its assertiveness in military, energy and economic matters, as well as in terms of its foreign policy to respond to these issues. By announcing a new Wende, the Zeitenwende (turning point), he intended to prepare the Germans for a new rupture of a magnitude comparable to reunification.

[...]

Rethinking relations with Eastern Europe and the Balkans

As a result of the war in Ukraine, the question of a new European security architecture is arising. The war marks the violation of the principles and spirit of the Charter of Paris for a New Europe, established in 1990. This consolidated Europe’s post-Cold War security architecture by condemning the “[…] threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State […]”. France and Germany, which have tried to find a political solution to the conflict between Ukraine and Russia since the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas, are increasingly being criticised for what has been deemed as hesitant support for Ukraine. They now must regain credibility in the eyes of some of their European (and American) partners in order to participate effectively in the new European security architecture.

[...]

European priorities on the Franco-German agenda

The Franco-German relationship has been institutionalised in the Elysée Treaty (1963) and the Treaty of Aachen (2019), which provide for a rapprochement of civil societies, institutions, and players in cross-border co-operation. Beyond that, Germany and France aspire to be the “engine of European construction”. However, the Franco-German couple is also marked by divergences in the European project that various crises, which multiplied from 2009, make increasingly apparent.

[...]

EU institutions are part of the equation

Certainly, the Franco-German duo has often given momentum to the EU’s political action, which undoubtedly requires political will and the assumption of leadership. If under this leadership the EU has shown itself able to quickly adapt over recent years to unforeseen events, notably during the COVID-19 pandemic, there are still calls to sustainably carry out structural institutional reform. The EU’s adaptability was exemplified by its suspension of applicable rules in state aid, the protection of its critical assets against unfriendly takeovers from third countries, the creation of the Next Generation EU Fund, and the temporary suspension of the Stability and Growth Pact.

[...]

Marie Krpata is Research Fellow, Study Committee on Franco-German Relations (Cerfa), Ifri.

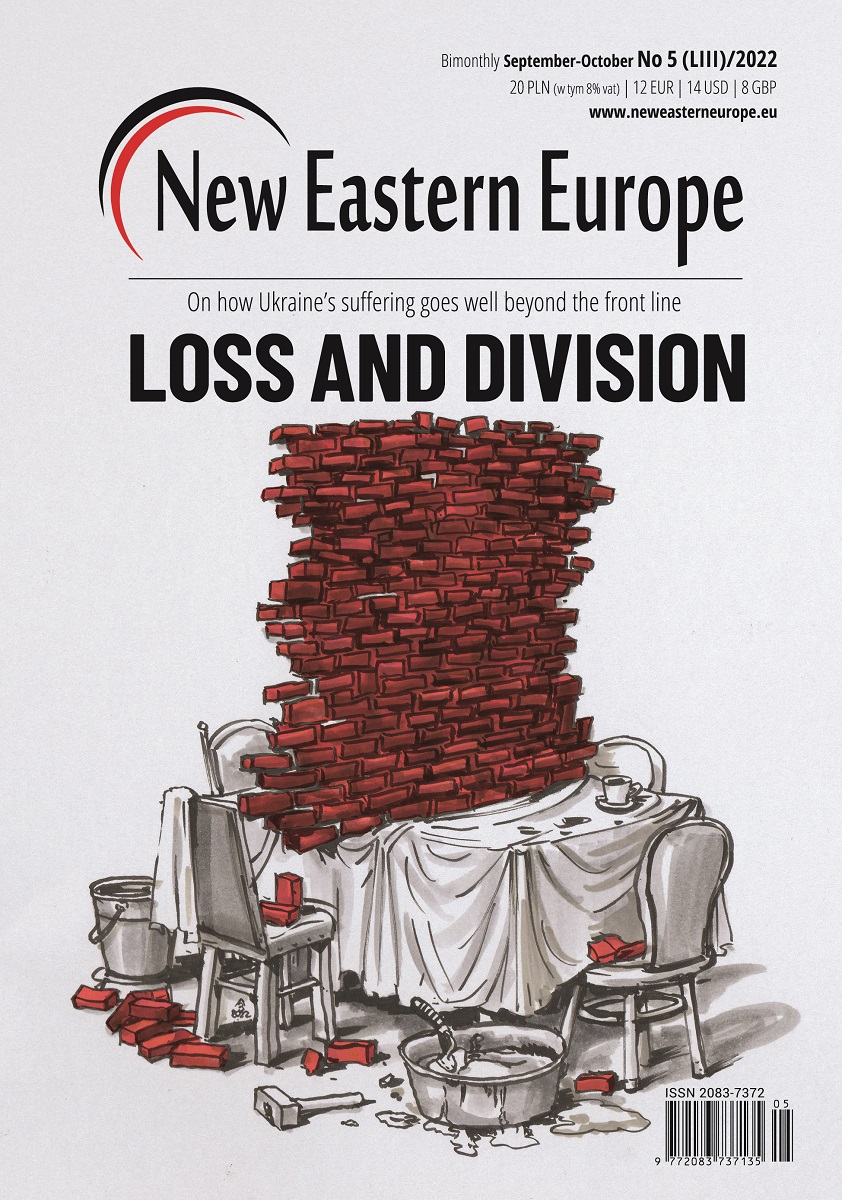

- This publication is published by New Eastern Europe. Issue 5/2022: Loss and Division.